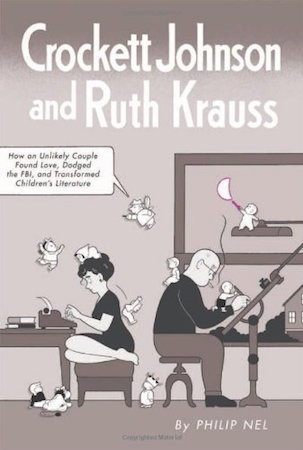

Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature

Catchy subtitle, isn’t it? Unfortunately, the book doesn’t quite live up to two-thirds of it. It’s a great picture of the life Ruth Krauss (noted children’s book author) and Crockett Johnson (Harold and the Purple Crayon, Barnaby) had together, but the FBI bit turns out to be some files due to the couple’s politics, and the last part isn’t explained fully enough for someone not already familiar with the field. However, as the first biography of either of them, it’s a wonderful start.

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed reading Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature. (All the more so since I’m still looking forward to the upcoming Fantagraphics reprint of Barnaby, now due in March or April. This book’s author, Philip Nel, is co-editing that book.) I found it fascinating that a number of leftists, finding it hard to get work elsewhere, moved into children’s literature in the 1950s. The genre wasn’t considered at all important, certainly not enough to police the authors, especially since so many of them were women.

I also didn’t realize that so many books I think of as classics (Narnia titles, Charlotte’s Web, various Dr. Seuss books) came out in that decade. Since I came along after, for me, they’d always existed. One was Harold and the Purple Crayon (and its six sequels), wonderful little illustrated volumes that demonstrate the possibilities of creativity, the ways imagination can be made real, and new ways to look at the world. (Note that the first Harold book came out in 1955, the same year as the similarly weird cartoon Duck Amuck.) Due to the timing of the baby boom, books for kids were having new heights of success.

Ruth Krauss’ breakthrough, it turns out, was creating books for kids that were expressed in their language and from their perspective, a distinction that’s particularly hard to recognize these days, since we’re so unfamiliar with the didactic, moralistic works that were the trend preceding. She was a struggling artist, occasional pulp writer, and anthropology student (training that informed her works in teaching kids anti-prejudice) before the two met in 1939; their later marriage was the second for both. The thing I’ll remember most about her was a brief mention of how she had “after-dinner narcolepsy”, sometimes falling asleep on the living room floor while entertaining guests after meals. (Doesn’t everyone get sleepy after a big dinner?) I thought I didn’t know any of her works, but it turns out I Can Fly was illustrated by Mary Blair (a favorite) and recently reprinted.

Johnson’s Barnaby comic strip, his first major work, ran from 1942-1952, although Johnson left at the end of 1945 and returned as the writer only in September 1947. It’s a cartoonist’s strip (the same way Leonard Cohen is a musician’s musician), full of subtle humor and cultural commentary, a specialized taste, never that popular, with a peak of 52 papers. It was the first comic to always use typeset dialogue, a choice I don’t always care for, but the author sees it as another sign of Johnson’s love of precision. Although a handful of strips are included in this book, the reproduction is light, which makes them somewhat hard to read. For a better idea of why the series was appealing, you’ll have to get the book dedicated to it. Before the strip, Johnson created radical progressive political cartoons for anti-fascist groups that arose as a reaction to the Depression but were considered highly suspicious by the red-baiting 50s.

Today’s readers may not understand why peace was such an unpopular subject during that past period of growing militarism and anti-communism, to the extent that those wishing for it were considered risks to be enemies of the state. So were those who thought society should be racially integrated. Now, it all seems a little silly. It’s also a sign of the times (that sadly hasn’t been fully corrected in society) that when the couple first worked on a book together (1945’s The Carrot Seed), the publisher didn’t understand why promoting the work as illustrated by Crockett Johnson and “written by his wife” was demeaning and upsetting.

As the book continues to follow their lives, there’s information on Krauss’ move into poetry and plays while Johnson began painting geometric theorems and discovered new math formulas through his visual explorations. (More reproductions of these would have also been appreciated. There are not nearly enough examples and illustrations included for a book about artists.) I found their story interesting as an example of how to build an artistic career and continually reinvigorate the creative impulse. What do you do after becoming a success? If you’re these two, you try a new field.

Given the author’s background in children’s literature studies, it’s not surprising that I left the book feeling that knew her more than him. Plus, she outlived him, which also means that more time is spent with her. The most lasting effect this biography will have on me will be the impulse to re-read my Harold books, which isn’t a bad thing at all. (The publisher provided a review copy.)

One comment